- Home

- Unternehmen

- Presse

- Grinding it out in Saskatchewan

Grinding it out in Saskatchewan

A new $90-million bioenergy facility has started up in Saskatchewan – and helping the power plant reach its feedstock goals is a custom-built wood hog grinder from Rawlings Manufacturing.

With the help of technical experts from Italy, Germany, Montana and the province of Saskatchewan, the First Nation Meadow Lake Tribal Council (MLTC) in Meadow Lake, Saskatchewan has now launched a state-of-the-art $90-million bioenergy facility.

The new power facility is producing enough energy to process the wood waste from their sawmill, power the bioenergy plant’s in-house facility (heat, lights and run the wood hog), provide power to 5,000 nearby city homes—and has enough energy left over to sell 6.6 megawatts to provincial utility, SaskPower Corporation.

MLTC is made up of nine independent tribes who come together to better manage services among their communities. Four are Dene tribes and five are Cree. Traditionally, the Dene people inhabit the northern boreal and Arctic regions of Canada, and the Cree occupy an area from the northern woodlands to southern plains.

While the two groups have distinct languages and distinct cultures, they have been dealing cohesively and effectively with issues around healthcare and education administration for 40 years. More than 30 years ago they started working toward matters pertaining to economic development.

Tina Rasmussen, tribal member and Project Co-ordinator, describes how the bioenergy project came about.

“Thirty-five years ago, the nine tribes decided to add an economic development arm to their existing healthcare, education and family service programs,” explained Rasmussen. “They purchased a 50 per cent share in a sawmill in Meadow Lake (called NorSask Forest Products), which had been producing kiln-dried 2 x 4s and 2 x 6s since the early 1970s. Within 10 years (1998), the Tribal Council purchased 100 per cent ownership of the mill and they have continued to operate it on a continuous basis.

“In order to ensure consistent timber supply, and make sure that the right timber reached the right mill, and that forest harvesting, planning, management, and reforestation practices were carried out effectively and efficiently, MLTC entered a partnership with a pulp mill in the area, Paper Excellence,” she added.

Between the two mills, they harvest the area’s spruce, fir, pine, etc., and process about 1.3 million cubic metres of timber annually. The hardwood goes to Paper Excellence and about half-a-million cubic metres of softwood comes to MLTC.

Each year, 56,000 tons of sawdust, bark, trimmings, and uneven chips from making lumber was continuously fed into the sawmill’s 50-year-old beehive burner (it is still legal to use it in Saskatchewan).

“The elders of the tribes had long believed that the waste of the tree residuals was not a good outcome, and the leadership was charged with trying to find a way to get benefit from the whole tree,” said Rasmussen. Thus, the idea for the MTLC Bio-Center was born. Construction of the new facility started in April, 2020, and it became operational earlier this year.

Al Balisky, a non-tribal member of MLTC Industrial Investments and CEO of the project since its inception, credits forward thinking among the tribal members of the nine First Nations, for the project.

“Saskatchewan has been a coal-based power producer and with this project, our carbon neutral waste stream is being turned into electricity,” Balisky said. “That’s been the big effort and I credit the MLTC for never having been afraid of trying new things and sort of punching way above their weight class.

“It’s been well over a dozen-year effort and the emphasis on green energy production throughout North America has made it easier. With federal and provincial supports in place, some of these projects come to life—plus the power utility for Saskatchewan has a real mandate to move to green power. Those two things coming together at the same time allowed us to do it

“COVID-19 has been disruptive, but we were able to work alongside the two-year construction project without any impact on the sawmill,” said Balisky.

“However, the pandemic did create havoc for us when it came to the equipment. The equipment used on site came from all over the world—vendors and suppliers for it were sourced from literally all over the world. That gave us a number of challenges.”

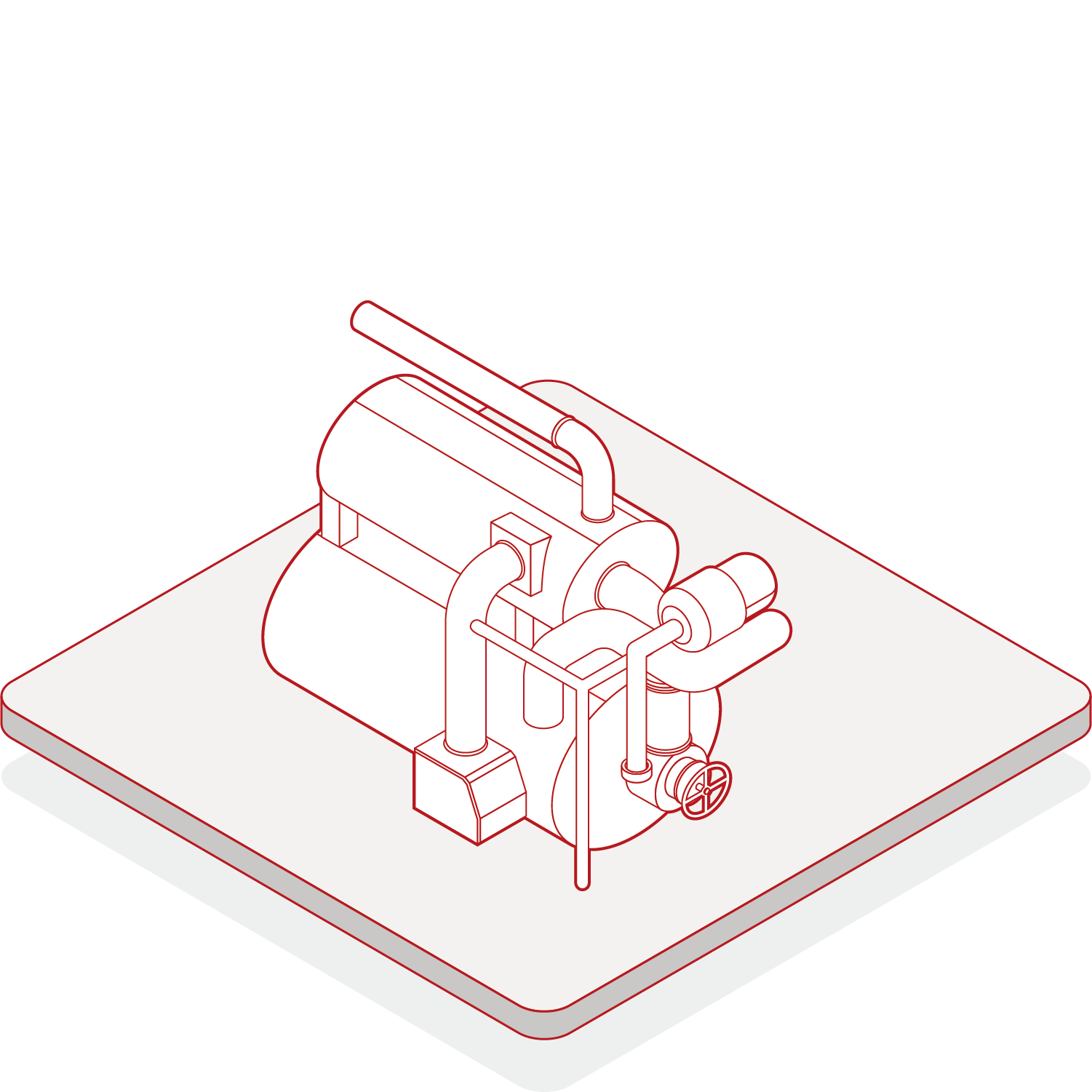

According to Rasmussen, the bioenergy thermal plant facility has a process similar to that of a thermal oil plant in a hotel or apartment that is heating water and transferring it in a way that causes the heat to be released. In this case, the wood waste comes out of the mill, goes through a Rawlings’ wood hog grinder so it gets ground to a uniform size, and is transferred by conveyor belt to a large storage silo.

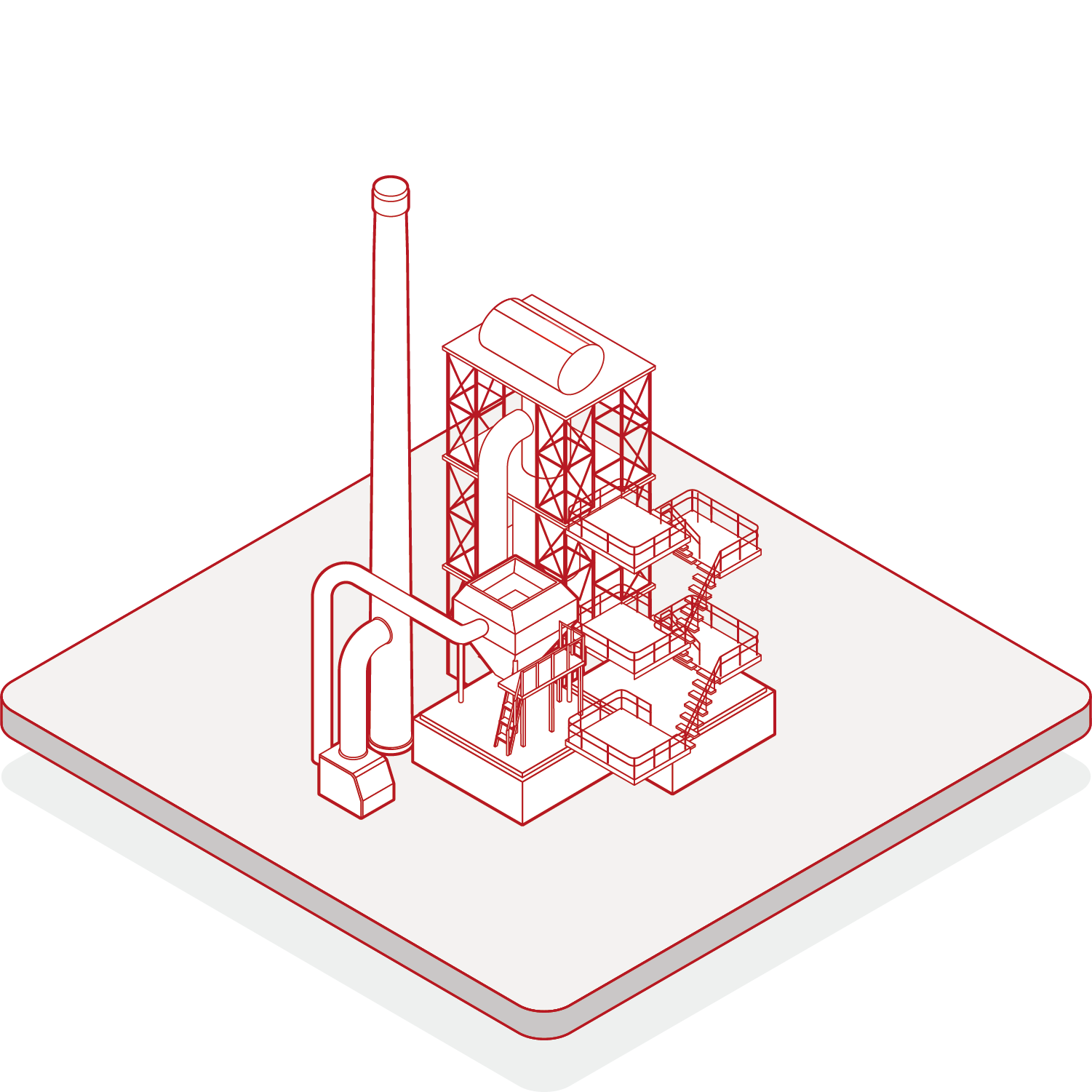

From there, those chips go on another conveyor and drop into the thermal oil plant which is basically a furnace. The furnace uniformly burns the wood waste. At the same time, there is a series of pipes that are channeled through that open flame and the thermal oil running through them is heated much in the same way as the boiler system in an apartment building.

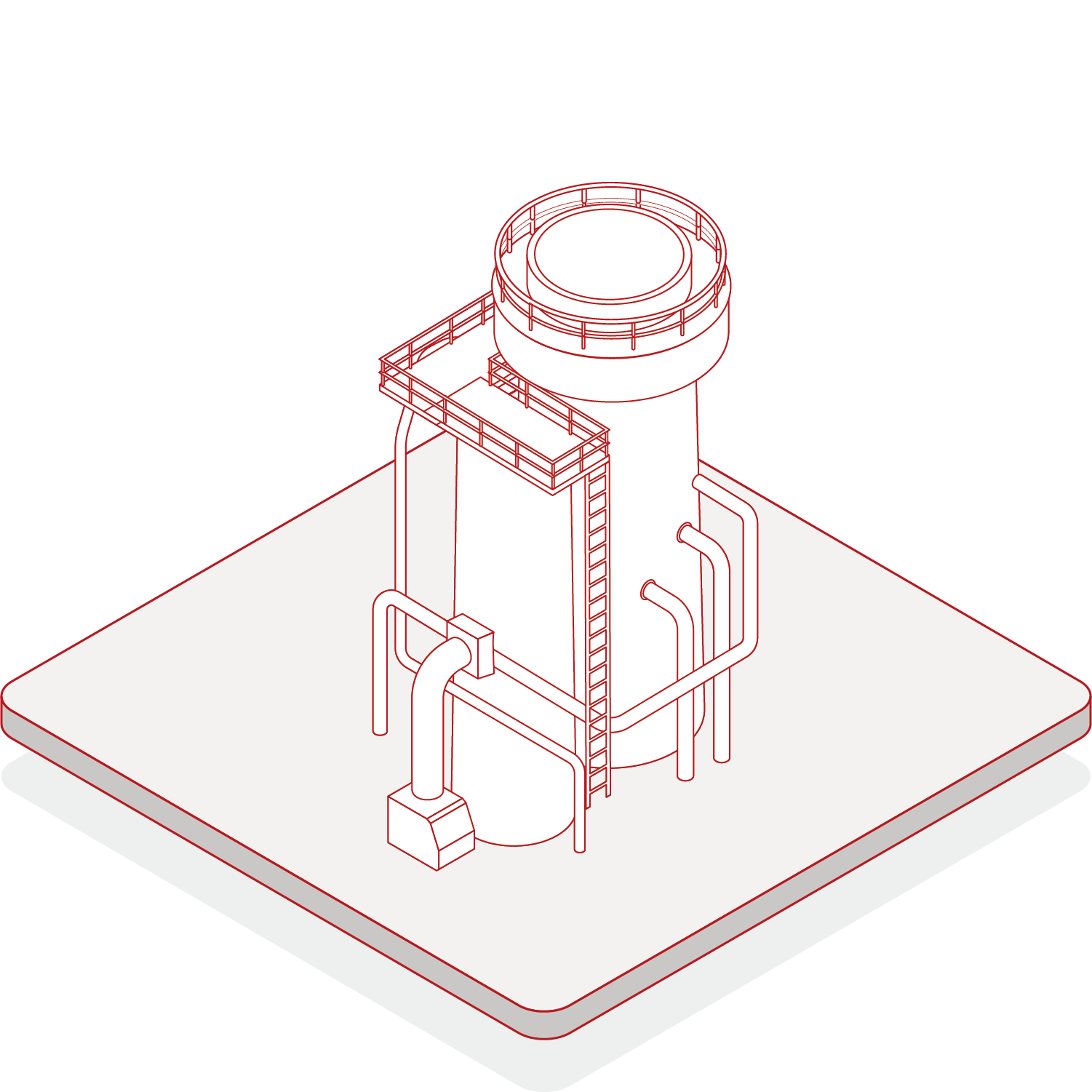

“Once the thermal oil is heated, it is transferred to our electrical building, and comes into contact with cyclopentane, the highly flammable alicyclic hydrocarbon consisting of a ring of five carbon atoms each bonded with two hydrogen atoms above and below the plane,” explains Rasmussen.

When cyclopentane hits a certain temperature and becomes gaseous, the gas effectively turns the turbine and creates electricity in the generator. This process produces 8.3 megawatts of electricity of which 6.6 megawatts is channeled out into a transformer station, and is fed into Saskatchewan Power Corporation’s power grid.

“Within that 8.3 megawatts, 1.7 megawatts are used to power the facility, operate the wood hog and the brand-new continuous dry kiln. In addition, the dry kiln receives its heat source from glycol heated in the thermal oil plant, then runs through the kiln replacing natural gas as a heat-based lumber drying source. This new kiln replaces two older natural gas dry kilns that were original to the sawmill. Now, we’ll have the ability to dry about 60 per cent of the lumber produced on a continuous basis in the mill.”

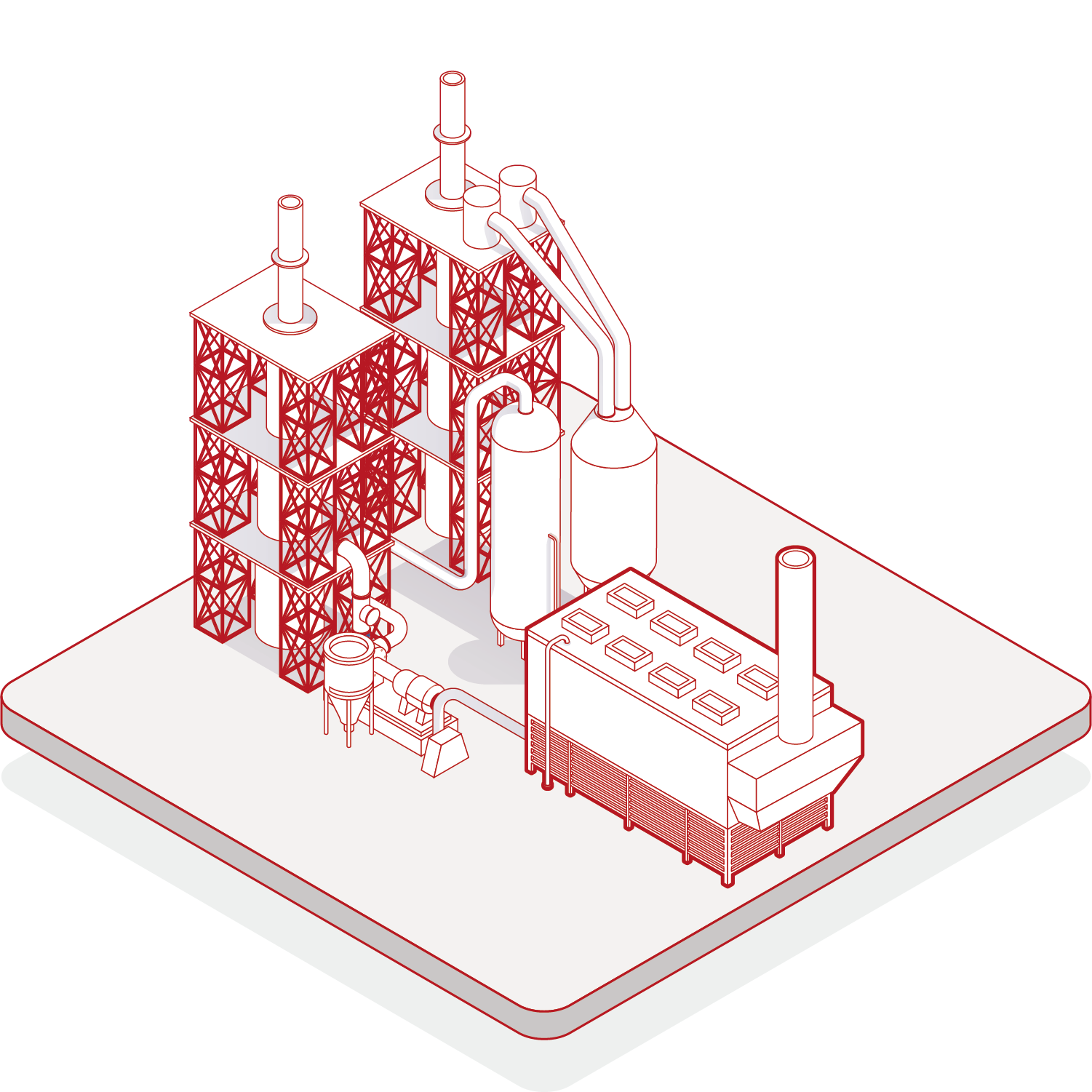

Mühlböck was selected as the supplier of the new continuous dry kiln. The company supplied MLTC with a Mühlböck 6-zone Progressive Flow 1306 PRO. This continuous kiln has the capacity to deliver about 85 million BF lumber per year, while Mühlböck’s unique 1306 Heat Recovery system ensures considerable reduction of thermal energy consumption.

To ensure a seamless fit of the fully automatic transport system within the kiln with the existing kiln cart system currently in operation at the sawmill, Mühlböck’s in-house engineers worked closely together with MLTC Bioenergy Centre.

The size and price of the entire bioenergy project was epic for what is technically a mom-and-pop sawmilling operation when compared in size and scope to many operations in Canada. The first step MLTC took to manage the development was to hire a project management company and engage a group of design engineers who had built other similar facilities. The First Nation firm of Whitecap Allnorth Project Group provided the consulting services and Grant Lindsay from a second First Nation firm, WGL Technical, led the design engineering team.

“The lion’s share of the $90 million construction cost went to buying technology and getting technology here,” Rasmussen said. “The thermal oil plant is a technology of Germany’s CAW (Classen Apparatebau Wiesloch GmbH), who designs terminal oil plants. To name the major pieces, the generator itself was designed by a company from Italy called Turboden, and the wood hog grinder came from Rawlings Manufacturing, Inc., out of Missoula, Montana.

“We went with Rawlings Manufacturing for the grinder because they are big in the forest industry and because they do their own in-house design,” said Rasmussen. “They looked at our wood supply, saw what the machine is going to have to chew up, and then designed a piece of equipment that could handle it. They are not just a one-size-fits-all company and it was important to us that they could build to suit.”

Rawlings Manufacturing specializes in the manufacture of custom-designed, industrial-sized wood waste recycling systems. Judy Tyacke-Rawlings, Rawlings Project Manager, said: “Once the design team is given the project parameters, we develop concept layouts to discuss with our clients, to develop and customize the wood grinding system to meet our clients’ specific processing needs and budget.

“This could include designing new systems for the specific customers or retrofitting existing systems. As a proven leader in size reduction equipment, we’re assisting our customers in utilizing renewable resources while reducing and recycling a wide variety of wood waste into valuable wood fibre products. Each system can be designed with work platform decks, choice of belt, chain or vibrating infeed and outfeed conveyors, metal or magnet protection, product screening and separation, receiving transfers and walking floor storage bins, all customizable for each specific operation.”

With over 45 years of experience in the forest and sawmill related industries, Rawlings Wood Hogs has delivered a reputation for durability, high performance and reliability.

They made the company an easy pick for MLTC.

As far as advice to anyone thinking about building a biomass plant, there are a lot of things to consider, says Rasmussen.

“We really had to weigh the business opportunity because it is extremely expensive. Originally, MLTC looked at a much larger facility but by the time we figured out biomass supply, the cost to get that waste out of the forest to the facility or get it from the other mill to the facility, it became so expensive that the financial opportunity was not there.

“In a nutshell, you must have access to the waste in close proximity. You need to build your facility size to what you produce in waste, and you need to have an offtake for the power so that you’ve got revenue coming in to help support the project.

“At the same time,” she added, “the facility needs to be built large enough to support your own processes. We did it because we had a resale for the energy and a government grant to partially support the project. Otherwise, the return on the financial investment would have been limited to heat and power for our own facility.”

By Jan Jackson / https://forestnet.com/

Classen Apparatebau Wiesloch GmbH

Ludwig-Wagner-Str. 9/1

D-69168 Wiesloch

Telefon | |

Telefax | |

Email | Diese E-Mail-Adresse ist vor Spambots geschützt! Zur Anzeige muss JavaScript eingeschaltet sein! |